In the Heart and Out in the World: A Profile of Artist David Coggins

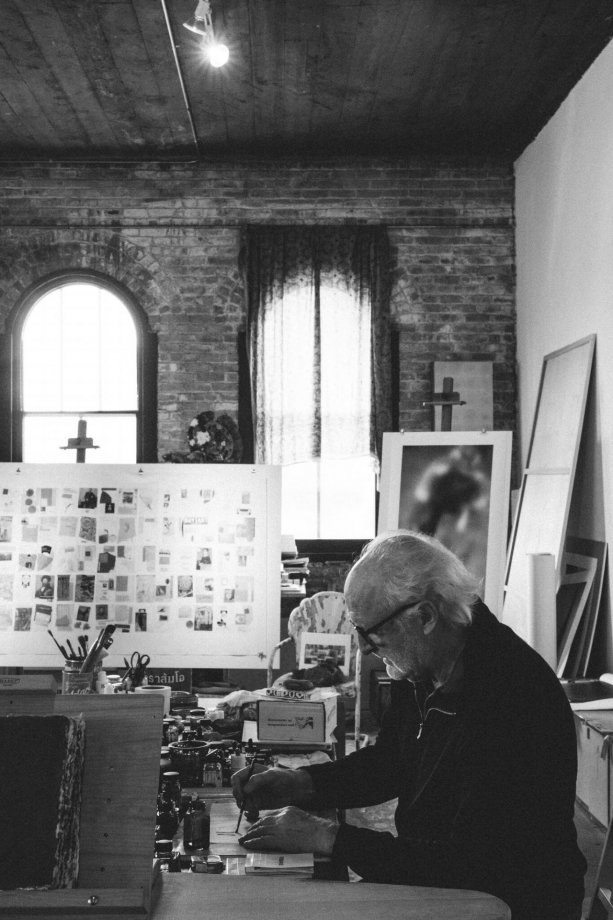

When David Coggins first moved into his studio in 1996, he thought he might keep it spare, minimalist.“It was such a beautiful, raw space,” he says, “with all those windows and nothing in it. I was just so wowed by it.”The room was part of the old warehouse for the defunct Grain Belt Brewery next door. It was massive, at 3,000 square feet. The outside walls were a beautiful, patchy brickwork with arched windows. Concrete columns ran floor to ceiling. It had an old-world, industrial feel, a remnant of another era.But those who knew Coggins shook their heads, knowing minimalism was unlikely. And, before long, the studio started to grow over with art and worldly objects. An old Spanish cabinet, small collections of stones, a plate of dice, spools of twine huddled together on a table.“I like to have beautiful things around,” Coggins says, “and old things, and important things and odd things that I’ve found over time that have meaning. I always love coming in, especially when I’ve been away. When I’m here, I don’t ever want to leave.”“When you step into that studio,” says Tom Rassieur, who curates prints and drawings at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, “it’s a transformative experience. You’re in this deeply personal, expansive, mesmerizing space. Your eye just goes everywhere. You feel like you could spend all day looking at these things that are a mixture of David’s own creations and things that he loves. It’s a Gesamtkunstwerk if there ever was one—an all-encompassing art work. In a sense, it’s a modern version of a 19th-century studio. It’s the most amazing environment.”Despite what one might think, the studio doesn’t feel cluttered or hoarded. There’s an order, a logic to it. The room has a geography of its own. It is like an ecosystem that grew out of Coggins’ mind, a world of his own making. And not long after he moved in, it took on a new importance to his career, a new prominence in his life. The world where he first found his artistic footing would begin to disappear.That old world was located across the river, in the warehouse district of Minneapolis. That was where Coggins had his first studio, his first show, his first taste of the artist’s life.It was a really vibrant scene,” says Jon Oulman, who owned a gallery there. “At one point, there were 16 art galleries in the Wyman Building, and 24 total in two blocks. We coordinated our openings at the same time so you could go to 15 or 20 galleries in an evening, and commune with like-minded people.”Coggins arrived on that scene in 1988, when he and his wife, Wendy, rented a large space that could be used for both her flower shop and his studio. It was just around the corner from the New French Bar, where it seemed like the entire local art world would gather at night to drink, gossip and talk about art.That studio was an open space. There was no door, so people could wander back and watch him work. When he put some paintings in Wendy’s flower shop, not only did people like them—they bought them. This was heartening for Coggins, who was just getting his start as an artist at the age of 35, a late-career transition.Before that, he’d made his living as a writer, doing freelance work for nonprofits, editing the Minnesota Orchestra’s program magazine, writing marketing copy and working on a novel on the side.But Coggins was never just a writer. “He’s always loved to draw,” Wendy says now. “He’d always done both. He studied art when we were in college, and afterward at the Art Institute of Chicago. When we lived in the Netherlands, he took classes at the Royal Academy. He always had a pencil in one hand and used a typewriter with the other.”The couple settled in Minneapolis in 1975 to start a family, and Coggins went to work on his writing. Their son and daughter were born soon after, and by the mid-1980s, the children were old enough for the family to start traveling again.They were staying in Paris with Minneapolis friend Dominique Serrand, who ran the Theatre de la Jeune Lune back home. Coggins was sitting at a window sketching the scene across the street when Dominique came up and looked over his shoulder.“Oh, I like that. I like how you add color when there isn’t color,” Serrand said.But to Coggins, the colors were clear. “I was adding bits of yellow and pink and blue because it was there. But, to his eye, it was just gray and brown.”When they returned to Minneapolis, Theatre de la Jeune Lune was producing Molière’s “The Bourgeois Gentleman,” and Serrand asked Coggins to paint the set. He spent the next two straight weeks painting the 18th-century interiors. “I loved it,” he says emphatically. “That was my moment of conversion. I said, ‘Okay, I’m going to paint.’”“I always knew he was talented,” says Wendy. “Art was always a passion for him, and you can’t keep someone from their passion. But whether you’re a writer or an artist, there is always the unknown.”“I just knew I had to do something different,” Coggins says, “and painting was something I’d always loved, and maybe should have done in the first place. It was a major decision and we talked about it endlessly, but Wendy was always supportive. She understood the needs and desires and frustrations. And it wasn’t like I was going from some high-paying job, giving up my six-figure salary. But it was a daily struggle. Every day, you ask yourself, ‘Should I really be doing this?’”So, the couple rented their space and Coggins’ paintings started to sell. When he’d gotten a bit of a reputation, he approached the Thomson Gallery around the corner, and the owner, Bob Thomson, agreed to take a few paintings. They sold. So, in 1990, he put on Coggins’ first show, and it sold out.“That was a huge boost,” Coggins says. “I thought, ‘Oh, great! This is going to work out.’”After that, he was contacted by dealers from Los Angeles, Dallas and Chicago. He kept working and selling. Then in 1995 he got an artist’s grant from the St. Paul Companies, Inc., to photograph the world’s great cities at the dawn of the internet. “My goal,” he says, “was to go to the hearts of the cities, to the old squares where it all started. Because in the future, the ‘square’ of the computer screen would be where people got together.”Over the next year, Coggins took more than 10,000 photos on 35mm film in cities like Cairo, Tokyo, Delhi, Istanbul, Barcelona, Prague, Berlin, Lima, Quito and Buenos Aires. He tried to capture the people, the plazas, the energy, the images, the minutia of late-20th-century life. “I was feeling like in the future, we were going to lose our face-to-face contact in these public places.”Back home again, Coggins settled into his new studio, where he developed his photos, then tore them, scratched and inked them until they appeared weathered and dark. Some he made into large, cubist collages. Others he mounted on Masonite tiles and installed them in what he called “Pascal’s Room,” after the philosopher who said, “The sole cause of man’s unhappiness is that he does not know how to stay quietly in his room.”This combination of disquiet and repose runs though many of Coggins’ projects. “David’s work has always been in the heart and out in the world,” says former gallery owner Oulman, who hosted the showing of the photos, titled “The Nostalgic Heart.” “And there’s an audience for that, because a lot of people feel that way.” “David is someone who is well-traveled and interesting,” says Eric Dayton a restaurateur, entrepreneur and a collector of Coggins’ work. “But he’s also really rooted in simplicity. He spends his summers at his cabin in Wisconsin. He’s grounded in nature and simple pleasures, but can go enjoy the great pleasures of a city like Paris. That’s reflected in his work, and probably why I like it.” “There’s an exploratory quality, both in the man and the work, that I find really engaging,” says poet G.E. Patterson, “There’s also a quality of reflection that I think is pretty consistent, and carries through the painting, the photography, the collage, the set design and also the writing. He’s been an influential figure in the work of other artists I know. A lot of poets are also very inspired by his work.”Dobby Gibson, whose new collection, “Little Glass Planet,” will be published later this year, is one of those poets. The first time he saw Coggins’ work was in a homeware shop.“He had a couple of ink drawings on the wall that just kind of stopped me in my tracks,” Gibson says. “When I saw them, I asked, ‘Who made those?’ I remember they were just ink marks on a canvas or a sheet. Some of his work has that kind of hypergraphia, that compulsive mark-making. Cy Twombly is another artist who has that. I think writers like artists like that, because it’s visual art that blurs toward writing.”Not long after he got back from his year of wandering city squares, his own city started to change. Rents went up. Corporate art buying went down. Galleries started to close. And before long, the warehouse district ceased to be the center of the art world.This was part of a broader shift as well, from an art scene centered around galleries to one more based on studios, private parties, private showings and the occasional art crawl, where artists open their doors to the public.When the Thomson Gallery shuttered in 1997, it was a serious blow to Coggins. He had already rebooted his career once, and now it seemed that he might have to start over again. He looked around for another gallery to call home. But in the end, he decided to focus on his studio—his Gesamtkunstwerk—and what he could produce in it. In 2004, he held his first show there and sold enough work that it seemed like it might work out ... again. At the same time, he had built a second studio at the cabin owned by Wendy’s family, on Pine Lake, Wisconsin.In the summer of 2009, he was walking through the woods around Pine Lake with his son, David (who is also a writer, and author of the forthcoming “Gentlemen, Behave!: Manners for the Modern Man”) when he felt a pain in his chest. He sat down, felt tired, and didn’t want to walk any more. His son ran off to get help, then drove him to a local hospital. From there, he was flown to a hospital in a larger city. Along the way, Coggins had time to think about all the work he still wanted to do.“I always had it in mind that I wanted to do something with our time in Paris,” Coggins. “Then you get older. Then you’re in a helicopter, flying through the night to a hospital and they’re rushing you into surgery. You realize that you need to get the things that you really want to do done.”In the end, it turned out Coggins’ heart was fine. The attack was minor and may have been related to stress. But the incident did change the course of his work. He decided to take a more contemplative, less combative approach to making art. First, he embarked on a series of line drawings, which he called “Yoga,” in lieu of actual yoga.“The Yoga drawings are pattern drawings,” he says. “They’re repetitious. They’re meditative. It’s a whole different way of working. Before it would be the long, arduous process of working on the canvas. I always wanted the painting to be the result of a conflict within myself about which direction it should go, and never being satisfied. But when it’s ink on paper, you’re just putting down the marks. You’re not reworking it, you’re not erasing. Maybe you have second thoughts, but you let it go, then you realize you didn’t need to have those second thoughts.”Coggins has also been more focused on books and memoirs. In 2009, he published a limited printing of “Birds of Pine Lake,” and in 2010 he published an eight-volume set of his “Daybooks,” which are small collages he makes in leatherbound notebooks. In 2012, he published “Breath,” about his father’s death. Then in 2015, he finally published “Paris in Winter,” his memoir in words and watercolors of the family’s stays there between 1997 to 2010. Currently, he’s working on another memoir about the island of Saint Barthélemy in the Caribbean, where his family spends a few weeks each year. After that, he’s planning a memoir about Pine Lake.“When I did my early landscape paintings, they were all inspired by where I am now, at Pine Lake. Because when I look out, there’s this big expanse of water and trees and the sky above. It’s these very fundamental, very powerful elements.”When we left his studio, Coggins got in his car and drove back to the lake, where he will work until he must close it down for the winter. Then, he will pack up his brushes and return to his “total work of art” in Minneapolis, where he will keep painting and writing. “I have gotten more productive over time,” Coggins says. “Because time is finite. When I started out, I wanted to be a great painter, and I still do. But from the very beginning, whether I was writing a novel or making a painting, I wanted to create something important and meaningful, that makes a difference in some way. I don’t need to make a zillion dollars. If someone comes up to me and says they loved something, that’s all I need. That’s the gift. That’s why I’m doing it.” This story originally appeared in ALIVE Issue 6, 2017. Purchase Issue 6 and become an ALIVE subscriber.Photography by Attilio D’Agostino.